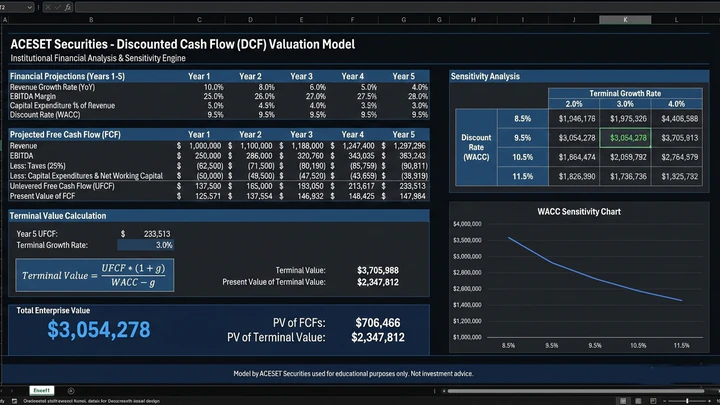

The Discounted Cash Flow model is one of the most widely used methods in finance to estimate the value of an investment, company, or project. At its core, the DCF model is built on the principle that the value of money changes over time — a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. By applying discounting techniques, we can translate future cash flows into their present value, allowing investors, analysts, and academics to make informed decisions.

This article provides a comprehensive academic and financial explanation of the Discounted Cash Flow model, with examples, practical insights, and advanced applications.

Discounted Cash Flow in One Minute

What DCF is: The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model is a way of estimating what an investment is worth today by translating all its future cash flows back into present value.

Why investors use it: Investors rely on DCF because it gives them an intrinsic measure of value, independent of market hype or short‑term volatility.

What you’ll learn in this guide:

- How the time value of money underpins DCF

- The step‑by‑step formula and its components

- Real examples of company and project valuations

- Practical tips for applying DCF in finance and investment decisions

- Comparisons with other valuation methods like multiples or asset‑based approaches

Outcome statement: By the end, you’ll know how to estimate what a stock, project, or business is worth today — using the power of Discounted Cash Flow.

Introduction to Discounted Cash Flow

The Discounted Cash Flow model is a valuation technique that calculates the present value of expected future cash flows. It is based on the principle of the time value of money, which states that money available today is worth more than the same amount in the future due to its earning potential.

By discounting future cash flows back to today using a discount rate (often the cost of capital), the DCF model provides a clear estimate of intrinsic value.

The 4 Ingredients of a DCF Model

Before diving into formulas, it’s important to understand the conceptual building blocks of a Discounted Cash Flow model. These four ingredients form the foundation of every DCF analysis.

Cash Flows

Cash flows are the lifeblood of the DCF model. They represent the money a business generates and can distribute to investors.

- Operating Cash Flow: The cash generated from day‑to‑day business operations (sales minus expenses).

- Free Cash Flow (FCF): The cash left after covering operating costs and necessary investments (like equipment or expansion). This is the most common input for DCF because it reflects what’s truly available to shareholders or debt holders.

Think of cash flows as the “fuel” that powers the valuation engine. Without them, the model has nothing to discount.

Time Horizon

The time horizon is the forecast period over which you project cash flows.

- Typically ranges from 5 to 10 years.

- Shorter horizons may be used for projects with limited lifespans.

- Longer horizons are rare because forecasting becomes less reliable the further you go.

Conceptually, the time horizon is about balancing detail with realism. You want enough years to capture meaningful growth, but not so many that your assumptions become speculative.

Discount Rate

The discount rate is the lens through which future cash flows are viewed today.

- Represents both risk and opportunity cost.

- Higher risk → higher discount rate → lower present value.

- Lower risk → lower discount rate → higher present value.

In simple terms, the discount rate answers: “What return would investors demand to put money into this business instead of somewhere else?”

Terminal Value

Terminal value captures everything that happens after the forecast period.

- Since businesses don’t stop after 5–10 years, terminal value estimates the continuing worth of the company.

- It often makes up the majority of a DCF valuation.

- Conceptually, it’s the “long‑tail” of the model — the value of all future cash flows beyond the explicit forecast.

Terminal value ensures the DCF doesn’t abruptly end at year 10, but instead reflects the ongoing nature of a business.

Putting It Together

These four ingredients — cash flows, time horizon, discount rate, and terminal value — are the conceptual prerequisites for any DCF model. They work together to translate future expectations into present‑day value.

How DCF Works (Step‑by‑Step Overview)

To give you a mental map before diving into formulas, here’s the conceptual walkthrough of how a Discounted Cash Flow model unfolds:

- Estimate Future Cash Flows

- Begin by forecasting the money a business or project will generate in the coming years.

- These are usually free cash flows, representing what’s left after covering operating costs and investments.

- Choose a Discount Rate

- Select a rate that reflects both the risk of the investment and the opportunity cost of capital.

- This is the “filter” that adjusts future money into today’s terms.

- Discount Future Cash Flows to Today

- Apply the discount rate to each year’s forecasted cash flow.

- This step translates future expectations into present value.

- Add Terminal Value

- Since businesses don’t stop after the forecast horizon (often 5–10 years), calculate a terminal value to capture everything beyond.

- This ensures the model reflects the ongoing nature of the business.

- Compare Intrinsic Value vs Market Price

- Sum the discounted cash flows and terminal value to get the intrinsic value.

- Compare this with the current market price to decide if the investment is undervalued, fairly valued, or overvalued.

Example: Valuing a Coffee Shop with DCF

Imagine you’re considering buying a neighborhood coffee shop. You want to know what it’s worth today. Here’s how the DCF process unfolds conceptually:

- Estimate Future Cash Flows

- You forecast that the shop will generate about $50,000 in free cash flow each year for the next 5 years.

- These cash flows represent money left after covering rent, salaries, supplies, and reinvestment in equipment.

- Choose a Discount Rate

- Because running a coffee shop carries some risk (competition, changing tastes, rising costs), you decide on a 10% discount rate.

- This reflects both the risk of the business and the return you could earn elsewhere (say, in the stock market).

- Discount Future Cash Flows to Today

- Conceptually, you’re asking: “What is $50,000 received in year 3 worth today?”

- Each year’s cash flow is adjusted downward by the discount rate, so future money shrinks when viewed in present terms.

- Add Terminal Value

- After year 5, you don’t expect the shop to suddenly close. You assume it will continue generating cash flows indefinitely.

- To capture this, you calculate a terminal value — essentially, the value of all cash flows beyond year 5.

- This ensures the DCF reflects the ongoing nature of the business.

- Compare Intrinsic Value vs Market Price

- You add up the discounted cash flows plus the terminal value.

- Suppose the total comes to $400,000.

- If the seller is asking $350,000, the shop looks undervalued. If they’re asking $500,000, it looks overpriced.

Watch Video Explanation by Warren Buffet

Core Formula of Discounted Cash Flow

The general DCF formula is:

Where:

- = Cash flow at time

- = Discount rate

- = Number of periods

The Time Value of Money

The foundation of DCF lies in the time value of money.

- Present Value (PV): The value today of a future sum of money.

- Future Value (FV): The amount of money expected at a future date.

- Discount Rate (r): The rate used to translate future cash flows into present value.

- Periods (t): The number of time intervals (years, months) until the cash flow occurs.

Formula:

This formula shows how negative exponents naturally appear in discounting.

Read more about Present Value vs Future Value

Worked Examples of Discounted Cash Flow

Example 1: Single Cash Flow You expect $10,000 in 3 years. Discount rate = 8%.

Example 2: Multiple Cash Flows Cash flows: $5,000 annually for 3 years. Discount rate = 10%.

Common DCF Mistakes Beginners Make

Even though the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model is a powerful valuation tool, beginners often stumble on a few recurring pitfalls. Highlighting these mistakes not only builds credibility but also shows readers that you understand the nuances of applying DCF in practice.

1. Unrealistic Growth Assumptions

- The Mistake: Assuming a company will grow at very high rates indefinitely.

- Why It Matters: No business can sustain double‑digit growth forever; markets mature, competition increases, and costs rise.

- Better Approach: Use conservative, industry‑aligned growth rates and taper them down over time.

2. Arbitrary Discount Rates

- The Mistake: Picking a discount rate without justification (e.g., “I’ll just use 10%”).

- Why It Matters: The discount rate reflects both risk and opportunity cost. An arbitrary choice can distort valuation.

- Better Approach: Derive the discount rate from the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) or required return benchmarks.

3. Blindly Trusting DCF Outputs

- The Mistake: Treating the DCF result as absolute truth.

- Why It Matters: DCF is highly sensitive to assumptions. A small tweak in growth or discount rate can swing valuation dramatically.

- Better Approach: Treat DCF as a range of values, not a single number. Always cross‑check with market multiples and qualitative factors.

4. Ignoring Sensitivity Analysis

- The Mistake: Presenting one DCF outcome without testing different scenarios.

- Why It Matters: Investors need to see how valuation changes under optimistic, base, and pessimistic assumptions.

- Better Approach: Run sensitivity tables (e.g., varying discount rates and growth rates) to show how robust the valuation is.

5. Overreliance on Terminal Value

- The Mistake: Letting terminal value dominate 70–80% of the total valuation.

- Why It Matters: This makes the model less about actual forecasts and more about long‑term guesswork.

- Better Approach: Ensure the forecast period captures meaningful cash flows, and use conservative assumptions for terminal growth.

6. Neglecting Real‑World Factors

- The Mistake: Building a DCF in isolation, ignoring industry cycles, regulation, or competitive dynamics.

- Why It Matters: Numbers alone don’t capture risks like technological disruption or policy changes.

- Better Approach: Combine DCF with qualitative analysis — management quality, market trends, and competitive positioning.

Comparisons with Other Valuation Methods

| Method | Basis | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCF | Present value of cash flows | Intrinsic, forward-looking | Sensitive to assumptions |

| Multiples | Market comparables | Quick, easy | Ignores future growth |

| Asset-based | Net asset value | Useful for liquidation | Ignores earning potential |

Is DCF Reliable? When to Use It (and When Not to)

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model is a powerful valuation tool, but it isn’t a universal solution. Its reliability depends heavily on the type of business and the predictability of future cash flows. Understanding when DCF works — and when it doesn’t — is crucial for applying it responsibly.

When DCF Works Best

- Stable, Cash‑Generating Businesses

- Companies with consistent revenues and predictable expenses are ideal candidates.

- Examples: utilities, consumer staples, mature manufacturing firms.

- Why: Their cash flows are easier to forecast, making the DCF outputs more reliable.

- Long‑Term Projects with Clear Cash Flow Structures

- Infrastructure projects (like toll roads or power plants) often have steady, contractual cash flows.

- Why: Predictability reduces the risk of error in forecasting.

- Established Companies with Historical Data

- Firms with a long operating history provide analysts with reliable trends.

- Why: Past performance helps anchor future projections.

When DCF Is a Poor Fit

- Early‑Stage Startups

- Startups often have negative or highly uncertain cash flows.

- Why: Forecasting growth and profitability is speculative, making DCF outputs misleading.

- Alternative: Use venture capital valuation methods or scenario‑based approaches.

- Highly Cyclical Companies

- Businesses tied to commodity prices, seasonal demand, or economic cycles (e.g., airlines, oil & gas).

- Why: Cash flows swing dramatically, and DCF struggles to capture volatility.

- Alternative: Normalize earnings or use relative valuation multiples.

- Businesses with Unpredictable Cash Flows

- Firms in industries facing disruption (like tech startups or fashion brands).

- Why: Rapid changes in consumer behavior or technology make long‑term forecasting unreliable.

- Alternative: Use option‑based valuation or market comparables.

Key Insight

DCF is most reliable when cash flows are steady and predictable. It becomes less useful when uncertainty dominates. In practice, analysts often combine DCF with other valuation methods to balance precision with realism.

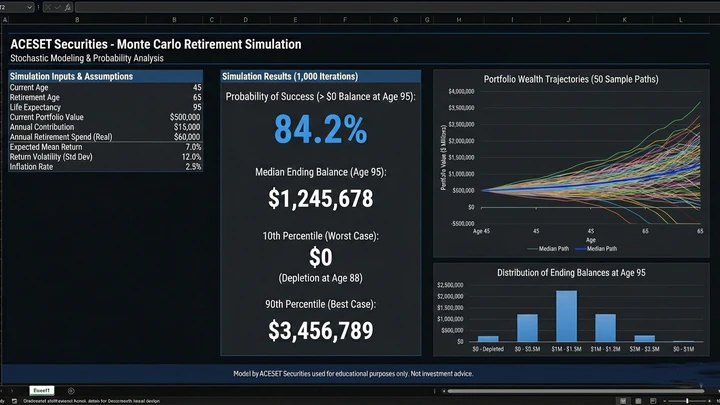

Practical Tips for Using DCF

- Be Conservative: Use realistic assumptions for growth and discount rates.

- Check Sensitivity: Small changes in discount rate can drastically affect valuation.

- Compare with Market Value: DCF gives intrinsic value; compare with actual market price.

- Use Scenario Analysis: Test optimistic, pessimistic, and base cases.

- Update Regularly: Recalculate as new data becomes available.

Advanced Applications of DCF

- Real Options Valuation: Extends DCF to account for flexibility in decision-making.

- Risk-adjusted DCF: Incorporates probability distributions for uncertain cash flows.

- DCF in Startups: Adjusted for high uncertainty and growth potential.

- DCF in Infrastructure Projects: Long-term forecasting with stable cash flows.

Behavioral Insights in DCF Usage

Numbers alone don’t explain why DCF models sometimes mislead. Human behavior plays a big role in how analysts and investors use — and misuse — the Discounted Cash Flow framework. Recognizing these behavioral tendencies helps build discipline and credibility.

1. Overestimating Growth

- The Bias: Analysts often assume companies will grow faster and longer than reality allows.

- Impact: Inflated growth assumptions lead to exaggerated valuations, especially when compounded over 5–10 years.

- Insight: Growth should taper over time. Mature businesses rarely sustain high growth indefinitely.

2. Anchoring on Discount Rates

- The Bias: Investors may fixate on a single discount rate (e.g., “10% is standard”) without testing alternatives.

- Impact: Anchoring blinds them to how sensitive valuations are to small changes in the rate.

- Insight: Always run sensitivity analysis with multiple discount rates to see how valuation shifts.

3. Blind Trust in DCF Outputs

- The Bias: Treating the DCF result as an absolute truth rather than a range.

- Impact: Leads to misplaced confidence in a single number, ignoring uncertainty in assumptions.

- Insight: DCF should be viewed as a range of possible values, not a precise figure.

4. Confirmation Bias in Assumptions

- The Bias: Analysts may unconsciously adjust inputs to match their desired outcome (e.g., making a stock look undervalued).

- Impact: This undermines objectivity and can justify poor investment decisions.

- Insight: Use independent benchmarks (industry averages, historical data) to ground assumptions.

5. Ignoring Qualitative Factors

- The Bias: Overreliance on numbers without considering management quality, competitive dynamics, or regulatory risks.

- Impact: Produces valuations that look precise but miss the bigger picture.

- Insight: Combine DCF with qualitative analysis to balance numbers with context.

Limitations of DCF

- Highly sensitive to discount rate and growth assumptions.

- Difficult to forecast cash flows accurately for long horizons.

- Terminal value often dominates results, reducing reliability.

Academic Perspective on DCF

From an academic standpoint, DCF is a practical application of mathematical finance. It demonstrates:

- The role of exponential functions and negative exponents in valuation.

- How discounting aligns with probability and risk-adjusted returns.

- The importance of assumptions in forecasting and modeling.

Financial Applications of DCF

In finance, DCF is used to:

- Value companies for mergers and acquisitions.

- Assess investment projects.

- Price bonds and securities.

- Compare intrinsic value with market value.

Conclusion

The Discounted Cash Flow model is a cornerstone of financial valuation and academic finance. By translating future cash flows into present value, it provides a rigorous framework for decision-making. While powerful, it requires careful assumptions, sensitivity analysis, and awareness of limitations.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is the discount rate chosen in a Discounted Cash Flow model?

The discount rate is typically the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) for companies, or the required rate of return for investors. It reflects the opportunity cost of capital and the risk profile of the investment.

What role does risk play in Discounted Cash Flow?

Risk is embedded in the discount rate. Higher risk investments require higher discount rates, which reduce present value. Analysts may also adjust cash flows directly for probability of occurrence.

How does Discounted Cash Flow differ from relative valuation methods?

DCF is intrinsic — it values an asset based on its own projected cash flows. Relative valuation compares a company to peers using multiples (like P/E or EV/EBITDA). DCF is forward‑looking, while multiples are market‑driven snapshots.

Why do analysts perform sensitivity analysis in DCF?

Because small changes in assumptions (growth rate, discount rate, terminal value) can drastically alter valuation. Sensitivity analysis shows how robust the valuation is under different scenarios.

Is Discounted Cash Flow always reliable?

DCF is powerful but not infallible. Its reliability depends on the accuracy of forecasts and assumptions. It should be used alongside other valuation methods for a balanced view.

Explore MORE ARTICLES